From 1975 to 1982 political

activity and the events that took place were so important that

professional matters were relegated to the back burner. One needed

to work and make money to cover basic needs, but the celebration,

the excitement, emotion and passion were out there on the

street.

The Referendum, the elections, the

legalization of political parties, electoral campaigns, the 23-F

(date of the military coup d'état) and many other events changed

Spain. The people of our generation feel as though we were

protagonists in all these events. My life at the side of Carmen

Rico Godoy was an ongoing experience at the forefront of all that

was going on in Madrid in that time. The first socialist meeting in

Canillejas, with Francois Mitterrand, Mário Soares and Felipe

González, the presentation of the CNT (National Confederation of

Labor) in San Sebastián de los Reyes, the festivities of the PCE

(Spanish Communist Party) in the Casa de Campo and demonstrations

against fascism, ultra-rightwing terrorism, etc., caused our lives

to fluctuate between extreme joy and sadness.

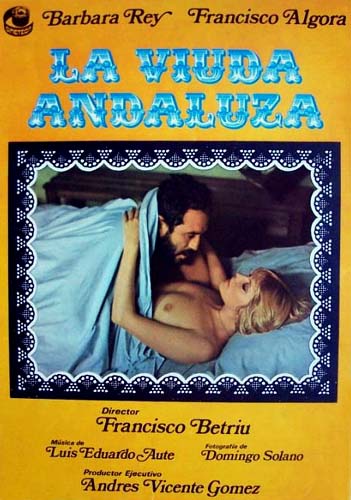

At the professional level, I

continued to intensify my work as a distributor and produced two

films about which I am very proud: "La viuda andaluza" (The Widow

from Andalusia) and "La verdad sobre el caso Savolta" (The Truth

about the Savolta Affair).

During this period, I was in

constant contact with journalists from the magazineCambio 16. One

of them, Xavier Domingo, had written a very comical and rude book

based on "La lozana andaluza" (The Portrait of Lozana: The Lusty

Andalusian Woman), the picaresque novel by Francisco Delgado about

which Vicente Escrivá had just made a successful film. Inspired by

that book and at my request, Francisco Betriu (whom I met after

placing a magazine ad for his first film "Corazón solitario") wrote

a hilarious script that we ultimately turned into a musical with

original songs by Luis Eduardo Aute. Bárbara Rey made her debut as

leading actress and part of an extraordinary cast which Tod

Browning would have wanted for his horror flick "Freaks" (1932). We

filmed for two months at the Ritz Hotel in Barcelona where I

discovered the concerts of the musical group, La Trinca in Canet,

and made new friends including Maruja Torres.

A magnificent review was published

inCambio 16on "La verdad sobre el caso Savolta" (The Truth about

the Savolta Affair), which I read and later met the author, Eduardo

Mendoza, in New York, where he was working as an interpreter.

At the time, Antonio Drove was

highly regarded and recognized as a talented director by some film

critics and technicians, particularly by the group known as "Los

Argüelleros". His prestige was supported by an excellent short film

he made, "Caza de brujas" (Witch Hunt), which was banned by the

management of the Escuela de Cine. He also directed a comedy for

José Luis Dibildos. I asked him to write the screen adaptation and

direct "La verdad sobre el caso Savolta". After a year of writing

the script, with Antonio Larreta, and a complicated editing process

of what was a co-production with Italy and France, we embarked on

one of the most ambitious projects in Spanish cinema, from a

creative and financial point of view, of the 1970s. It was a movie

I wish I could make over now because, at the time, it was too big

for me as a producer. I financed it with the income from two film

purchases: "Padre Padrone" and "Libertad sexual en Dinamarca". In

order to produce the movie, I set up a production company, Domingo

Pedret, S.A., and a distribution company, Cinema 3, S.A. together

with several partners from Barcelona, with Juan Torras, from the

famous company Torras-Hostench, amongst them.

The filming was very problematic,

with serious differences between Pedret and Drove; they were

eventually resolved. When the movie was finally released, those who

saw it have praised it ever since. Most likely, this film marked

and conditioned Antonio Drove's future as a filmmaker. Despite news

media reports about differences between us, I always felt great

affection for Antonio and considered him to be an excellent

professional. Whenever the opportunity presented itself, I have

expressed my interest in working with him again. In fact, we hired

him years later as co-scriptwriter for the screen adaptation of "El

embrujo de Shanghai" (The Shanghai Spell) which he started writing

with Víctor Erice.

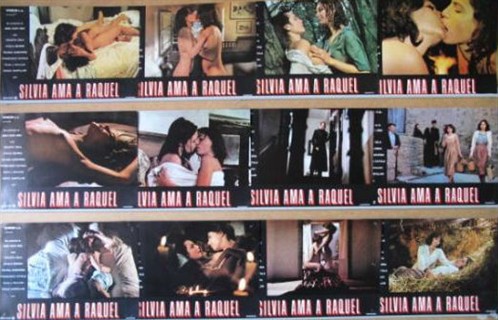

My relationship with Diego

Santillán, the loosening of censorship in Spain and the commercial

success of erotic films from abroad, encouraged me to produce

"Silvia ama a Raquel" (Silvia loves Raquel), a story about two

lesbians. One of the leading characters was Violeta Cela, who later

on worked with me in "El año de las luces" (The Year of

Enlightenment) and in the 1990s became famous as a promoter of

erotic telephone lines. The finishing touch of a decade of blunders

as a producer came when "confused and influenced" by bad company, I

produced a monstrosity of a film, stupid and lacking in substance,

called "Cocaína" (Cocaine). It was an homage to photographer Julio

Wizuete, whose wife died in a car accident on Km 301 of the road

between Madrid and Andalucia in which I too had been involved. I

don't recall having ever seen the film, which was never of interest

to me and I still don't understand how I could have produced

it.

I have always thought that

producers and directors should never develop a relationship or

friendship with film critics. It is the only way of mitigating your

anger towards them, of not conditioning their work and, as actor

Santiago Segura would say, to avoid quarrels with buddies. My case

with Miguel Rubio was an exception. We used to live very near one

another and we both loved Real Madrid. Besides, Miguel was a

socialist and we shared that important sentiment. One day Miguel

received a telephone call from Ramón Mendoza, a famous wealthy

entrepreneur who, at the time, was being condemned byCambio 16for

being a collaborator and covering for Russian spies. Mendoza was

interested in getting to know the socialist leaders who were

opponents of the UCD government and also wanted to become president

of the Real Madrid soccer team. He thought that Miguel could help

him in attaining both goals. To obtain his collaboration, he

offered to go into business with him. Miguel asked for my advice

and help to offer Mendoza something from which we might both

profit. I suggested that he propose to Mendoza to finance the

purchase of foreign films. Shortly after, we set up a new company,

Intercine. Mendoza brought José Luis Ballvé, the owner of

Campofrío, into the company. He made space available for us at his

offices on Avda del Generalísimo Street, which space we were

supposed to share with the sons of well-known communist Santiago

Carrillo, Azcárate and Jorge Lacasa, all of them "Russian children"

(Spanish children sent to Russia during the Spanish Civil

War).

But it didn't take Mendoza long to

start suspecting, and rightly so, that Miguel and I were little

more than a couple of insignificant sympathizers of the PSOE (The

Spanish Socialist Party) and didn't have much to offer him. Our

relationship cooled and the business romance ended a few months

later. It was useful in that it enabled me to buy "Cristo se paró

en Éboli" (Christ Stopped at Eboli), directed by Francesco Rosi,

and a couple of other films of little relevance. I was also able to

pay outstanding debts for "Corridas de alegría" (Joyful Orgasms),

"Silvia ama a Raquel" (Silvia Loves Raquel) and "Cocaína"

(Cocaine), my latest productions. But I had to get back to reality

and so, from my comfortable office at La Castellana (then called

Avda Generalísimo), I moved to the tiny office I had on Trujillo 7

Street, near Sol district. As to Mendoza, he eventually became a

superb president of Real Madrid, and he invited me to his box at

the stadium when in 1994 we were awarded the Oscar for the film

"Belle époque".

"Corridas de alegría" -inspired by

the Japanese film directed by Oshima "Ai no corrida" (In the Realm

of the Senses) - was an attempt at making a road movie along the

lines of the American films from the 1970s that had made the genre

fashionable. Gonzalo García Pelayo, director and co-writer, got in

touch with me with his film project, "Frente al mar" (Facing the

Sea), which I renamed "Intercambio de parejas frente al mar"

(Couple Swinging Facing the Sea). It turned out to be moderately

successful. Gonzalo is a very peculiar character: a bohemian and

extremely realistic individual at the same time, a fundamentalist

from Seville, an artist and a dreamer though also practical, as

well as the father of dozens of children from many different women.

A multifaceted individual and a great producer of Andalusian music,

he was responsible for the big hits of singers María Jiménez, Lole

and Manuel and others.

"Corridas de alegría" was shot in

the South of Spain, following the journey of its protagonists, who

travel from Seville to Cadiz, crossing the Ronda mountain range and

Grazalema. The film was in praise of the free Andalusian spirit,

its amusing nature and poverty, a portrait of pre-democratic Spain

where elements of the Franco regime, though in decline, still

existed. It was a film that went unnoticed by the public due to

inefficient distribution and a poor launch, for which I blame

myself entirely - but which people like José Luis Guarner, the best

cinema critic of the last 50 years, considered to be a small

masterpiece.

In 1981 and 1982, I was dreaming

about a Socialist victory in the general elections. When it

happened and the fervor of the celebrations were over, I thought

about intensifying my work as a producer and not settle with just

making my living as a distributor. I still kept my small office on

7 Trujillo Street and was a neighbor of the notorious distributor

José Esteban Alenda. Also, I had a small team of collaborators,

with José Luis García and Juan Campos among them. Both José Luis

and Juan are still very close to me. Together, we achieved a great

deal of success as distributors, the most noteworthy of them being

"El último emperador" (The Last Emperor), and we managed to

consolidate a distribution network based on our regional agents

who, as we were their best suppliers, responded with interest and

good will to all of our collaboration proposals. They would make

advance payments to me involving large amounts of money through

bills of exchange. This made me an expert in the art of discount

(on note receivable and promissory notes) and banking finance while

at the same time enabling me to keep up a regular production pace,

something I had dreamt about for such a long time.

At the age of almost 40 and with 20

years of cinematographic experience, I had the urge to become a

great producer. My instinct advised me to make commercial films

that might enable me to make good profits without having to depend

on distribution activities to keep going. And making commercial

movies in those days meant having to approach one man in

particular: Mariano Ozores, the indisputable "king of the box

office". I convinced him to make two films with me, "Los caraduros"

and "El pan debajo del brazo". The first of these was signed by his

brother Antonio, although it was directed by Mariano because the

latter had an exclusive contract with Ízaro Films, which guaranteed

him four films per year. Mariano wasn't very busy at the time and

because of that he entered into an alliance with me. But soon

enough, my ideas about production clashed with his. I repeatedly

told him some basic things, such as filming with direct sound, to

ensure that the actors had learned their lines. In addition, I

suggested that he stop constantly repeating their part in the cast

and a few other little things that I deemed essential. My

relationship with Mariano was excellent but unfortunately my

"creative" contribution was detrimental for the marketing of the

type of films Mariano made and the two films were only moderately

successful. Perhaps I was too late when I resorted to Ozores

because it is true that, since then, he hasn't made any big box

office hits.

At the same time as the Ozores

situation went on, my relationship with Harry Alan Towers resulted

in the co-production of a series of films for the US-based Playboy

Channel. At the time, it was inexpensive to film in Spain. We had

$400,000 dollars at our disposal, per film, supplied to us by the

American company. With a French director, Claude Mulot, and a

Spanish director, Paco Lara Polop, we shot "La venus negra" (Black

Venus) and "Christina" respectively. We subsequently changed the

latter's name to "Christina y la reconversión sexual" (Christina

and the sexual restructuring), inspired by the industrial

restructuring which the Minister of Economy, Carlos Solchaga,

launched that year.