During the 1960s, many foreign movies were filmed in

Spain. Samuel Bronston made Spain fashionable and countless

technicians, actors, second unit directors and others in the

industry who weren't successful in the USA achieved a higher

quality of life in Madrid than they could have ever afforded in

their own country. Chamartín, and particularly the so-called

neighborhood of "Corea" (Korea), in the upper part of Dr. Fleming

Street, was full of such personalities. Bruce Yorke, an Australian

I met in London, introduced me to Gilbert Kay, a second unit

director in some of the movies filmed here. Kay was looking for a

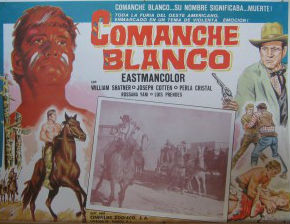

producer and handed me a script called "Comanche blanco" (White

Comanche). Westerns had become popular again thanks to the

financial stimulus Spain had given to the genre. I would like to

take this opportunity to remind readers that the first Western

movie to be filmed in Europe was "Tierra Brutal" (Brutal Land,

1961), produced by the Carreras brothers -owners of Hammer- and

coproduced in Spain by José G. Maesso. It wasn't the Italians, as

is commonly believed, who created this fashion. In order to produce

"Comanche blanco," Augusto Boué set up a new family production

company, Producciones Cinematográficas A.B., Sociedad Anónima, with

his wife and brothers-in-law as shareholders. I founded Baton

Films, S.A. and settled into one of the three offices on the

premises of the lawyer Alvaro Núñez M. Maturana in the district of

Argüelles, on Francisco de Ricci Street, No 13. The other two

offices were used by Alvaro and a recently graduated lawyer, José

Luis Sanz Arribas, who was single at the time, but not for long. He

was going out with Filín, whom he soon married and has remained so

until today.

Probably one of José Luis's first jobs was to

establish Baton Films. Since then he has helped me out of the many

messes I've gotten myself into over the nearly 40 years of our

professional lives together. If it were possible to measure

loyalty, the fidelity we professed towards each other would

certainly excel and the balance would surely be in his favor. His

support and help throughout these years has been enormous and the

affection and fraternity between us goes well beyond friendship or

a relationship of a client and his lawyer.

Obviously, "White Comanche" was to be a coproduction

between Producciones Cinematográficas A.B. and Baton Films. The

financial resources of A.B. amounted approximately to one million

pesetas and Baton Films' to two hundred thousand pesetas. Both

Augusto and I contributed towards the project with our work and

since I was the only one who spoke English, I acted as executive

producer.

The estimated budget of

the film was eight million pesetas, to which should be added the

salaries of the scriptwriter and co-director, Gilbert Kay, and the

actors, William Shatner and Joseph Cotten, which were paid by an

American production company based in London. The American company

in turn received funds from Westinghouse, the owner of several

local TV broadcasting stations in the USA. The film was co-directed

by Gilbert Kay and the Spaniard, José Briz.

The estimated budget of

the film was eight million pesetas, to which should be added the

salaries of the scriptwriter and co-director, Gilbert Kay, and the

actors, William Shatner and Joseph Cotten, which were paid by an

American production company based in London. The American company

in turn received funds from Westinghouse, the owner of several

local TV broadcasting stations in the USA. The film was co-directed

by Gilbert Kay and the Spaniard, José Briz.

Baton Films and A.B., through an accountant, Julián

Buedo, got in touch with Benito Aflalo, a Sephardi Jew and owner of

"pinball" machines, with certain financial resources and contacts

amongst the entrepreneurs from the Jewish community in Madrid. In

that way, with Benito Aflalo's money and the American

contributions, we started shooting the film in Colmenar Viejo, a

Western town near Madrid built as a set for the movie.

During the shooting, the Arab-Israeli conflict broke

out - the Six Day War. We encountered financial, creative, trade

union-related problems and all sorts of other difficulties, in

which I found myself involved and was able to resolve gradually,

despite my lack of experience and certain "juvenile arrogance". I

recall those days with nostalgia though also with some regret: I

was not sufficiently respectful towards some excellent people

around me who, because of their experience, had much to teach

me.

The film was sold, thanks to Aflalo's Jewish

contacts, mostly in Europe, so that he was able to recover his

investment. Augusto and I, on the other hand, failed to market the

film successfully in Spain and lost our investment. In his case the

main loss was the money of his family, and particularly the funds

supplied by film critic Luis Gómez Mesa. As for me, I lost my job

and became indebted to several suppliers. Eventually, the film's

negative went out to public auction at the request of the

laboratory that had custody of it. I could have retrieved the

negative many times subsequently with little money but frankly -

and this also applies to other negatives - I didn't (and don't)

feel the need to have the rights to these films just to prove to

myself or anyone else that I produced them.

Given my little success as a producer, and sorely

aware of the misery and poverty in the world, I undertook

preparations to make a full-length documentary film with the

intention of releasing it through theater houses. I worked with

José Briz, with whom I had developed a close bond and had also

promised him to produce a film as compensation for all the help he

gave me with "White Comanche." We gave the project the provisional

title of "El hambre en el mundo" (Hunger in the World). Through an

uncle of Briz, Manuel Méndez, we got in touch with UNICEF in Paris

for sponsorship purposes and they agreed. Our intention was to

report on and condemn the hunger that was widespread in most

developing countries. UNICEF introduced us into all the countries

we wanted to visit and we began filming in Uganda. We travelled to

Kampala, the capital, and from there, to Karamoya, near to the

border with southern Sudan. And there we witnessed extreme hunger,

though it didn't compare to the terrible urban misery we were to

encounter later on. We then went back to Spain, very impressed by

our experience. To judge from the images I see on television, the

situation is still horrendous 35 years later as the essentially

secret war between Uganda and Sudan continues to be ignored by the

"civilized" world.

Curiously enough, the film was being financed totally

by the owner of the Melodías Club, located on Desengaño Street in

Madrid. A character involved in small-scale real estate speculation

and businesses that revolved around prostitution, he gave us the

money to make the film - four or five million pesetas - in exchange

for taking his 20-year-old son with us to Africa. He was hoping to

get him into filmmaking and away from the local cops and crooks who

used to show up regularly at his night club and with whom he'd

already developed an unhealthy relationship.

Our second trip was to Peru. We travelled across the

Andes to Lake Titicaca, on the border with Bolivia. Our destination

was a crowded settlement known as "Little London" because of the

great multitudes who lived there. We were very impressed by the

grating poverty, the shacks crammed with families living amid

stinking waters and sick children coexisting with their dying

elders. All this, together with Machupichu, the Altiplano (high

plains), the llamas and the indigenous folklore, enabled us to see

a world that was full of contrasts.

Our third trip was to Pakistan and India; we toured

Calcutta, Benares, Karachi, Islamabad and the Himalayas for a

period of three months. We filmed thousands of rolls of footage

with a crew of five people: two cameras, sound (technician),

direction and production. We visited lepers' camps; we bathed in

the Ganges and ended up eventually with a film, which we presented

to UNICEF's New York office. However, the film was rejected on the

grounds that it was too sensitive and bound to offend the

governments of the countries we visited. According to our agreement

with UNICEF we were supposed to shoot a film presentation with

Robert Kennedy, but he was assassinated before we had a chance and

the film was never shown in public. Recently, I saw a black &

white copy of the film in its editing stages. The only usefulness I

found in it was to be able to show that those countries are worse

off today than they were 35 years ago. What Fromm predicted at the

time turned out to be true: the gap between the rich and the poor

is increasing and will continue to do so. During the shooting of

"El hambre en el mundo" we met Louis Malle, who was filming

"Calcutta," at Mother Teresa's Charity Center. His film, unlike

ours, saw the light of day.

Upon my return from India, married as I was, with two

children, aged three and two, I decided to give up the movie

business. To earn a living I got together with an employee from the

Banco Coca, a dreamer although also a very enterprising man who

wanted to do big international business. He was Manuel Michelena,

originally from Bilbao. He had some important contacts amongst

which were businessman José Lipperhide -who years later was

kidnapped by ETA-, and a Palestinian trader. All I had to offer as

a partner were my language skills. We tried to sell Romanian cement

to Argentina and Algerian oil to Germany. These big operations,

which in the end failed, took me to Beirut and Algiers. I met

sultans from the Persian Gulf and guerrillas from Al-Fatah. It was

all very exciting and brings back memories but I was quickly losing

faith in its usefulness and started to doubt that anything tangible

would materialize from our Spanish-Arab endeavors.

A few months later, Manolo Michelena introduced me to

Elías Querejeta, whom he knew as a client of the bank where he

still worked. Elías reawakened my interest in cinema and gave me a

job in his production company as a vendor of his films abroad. At

the time, Elías had finished "La madriguera" (Honeycomb), directed

by Carlos Saura, filmed in English and starring Geraldine Chaplin

and Per Oscarsson. He was looking for someone who spoke languages

and was willing to market it outside Spain.

This happened between 1969 and 1970. In those days,

Elías was a daring producer - the inventor of a new esthetic that

was close to high-quality European cinema - more in line with

Scandinavian films than Italian cinema. He was also a progressive

man who unsettled everyone around him because people took him for a

radical left-winger. Although we never developed a very close

personal relationship, Elías opened up a new professional and

fascinating world for me and, for many years, he remained a point

of reference as regards my work. Thanks to him I discovered that

filmmaking was a huge creative act as I became acquainted with the

new esthetic and ideological currents of cinema in those

pre-democracy years. Although I respect and have affection for some

of the producers I have met over the years, it is Elías Querejeta

that I most admire, despite the fact that when he played as a

footballer for Real Sociedad from San Sebastian he scored a goal

against the team I support - Real Madrid.

During the nearly two years I worked for Elías, I

travelled to a lot of Festivals and markets in cities all over the

world. I did a good job and managed to sell most of his films

wherever it was possible. But I continued to feel the urge to

produce films myself. I tried to do so in his production company,

under his protection and umbrella. Thus, while I carried on with my

marketing duties, at the same time I developed projects and

established links to launch films as a producer. Somewhat

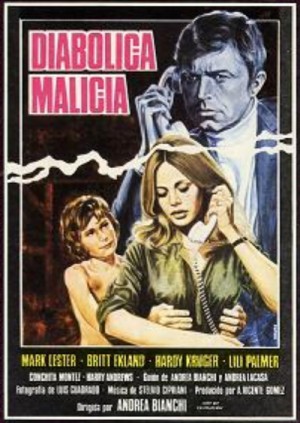

reluctantly, Elías allowed me to coproduce "Belleza negra" (Black

Beauty) and "Diábolica malicia" (Night Child), which were my first

collaborations with Englishman Harry Alan Towers, now a legendary

producer of "B" films, with whom Nick Wentworth worked as an

editor. Elías proposed that I buy a commercial name - Eguiluz Films

- to draw a line between such "half-dirty businesses" and Spanish

co-productions that were close to intellectual art house movies,

which he personally dealt with. Profit-wise, the breakdown was 75%

for Elías and 25% for me. Thanks to selling films abroad and the

proceeds from the "half-dirty co-production businesses" in which

the quality of the film was what mattered least, I made so much

money then that some of Elias' close acquaintances and friends

didn't forgive me. Eventually I found myself in a very

uncomfortable position because of that, which ultimately led me to

pull out and work on my own. However, the businesses I started

under the umbrella of Querejeta were so numerous and varied that

when I left his production company I had a considerable amount of

cash, plus the production company Eguiluz Films and the complete

RKO film catalogue (600 short films and 750 feature films).

Elías brings to mind some very happy moments. When I

worked for that man I felt great affection towards him and his

whole environment. There was a mutual understanding and complicity

between us. I think he sincerely trusted me, to the extent of

leaving his daughter Gracia (who at the time was six or seven years

old) under my care during her trips to England where she was going

to boarding school. I used to travel with her during such trips and

we'd stay overnight in London together.

The info about "Diabolica

Malicia" and "Belleza Negra" figure in my filmography and I haven't

much to say in that regard other than when the films were shot, I

met and became a close friend of Luis Cuadrado and Teo Escamilla,

two of the greatest directors of photography in this country with

whom I had the pleasure of working. Sadly, both are now dead.

The info about "Diabolica

Malicia" and "Belleza Negra" figure in my filmography and I haven't

much to say in that regard other than when the films were shot, I

met and became a close friend of Luis Cuadrado and Teo Escamilla,

two of the greatest directors of photography in this country with

whom I had the pleasure of working. Sadly, both are now dead.

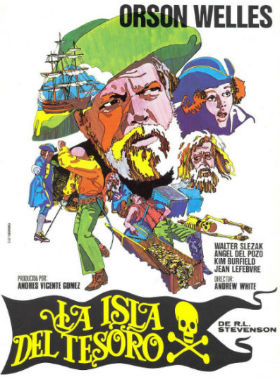

But "Belleza negra" and "Diábolica malicia", whose

physical production I was almost exclusively in charge of, offered

me the opportunity to acquire considerable experience and above all

prove that I could handle difficult situations with international

actors, co-productions involving different countries and foreign

directors. Harry Alan Towers, an active man with several films

going in different continents and a special antagonism towards

filming and its associated problems, entrusted me fully with the

responsibility for successfully finalizing the movie "La isla del

tesoro" (Treasure Island), a Spanish-Italian-German-French-English

coproduction, made for a North American distributor. There were so

many foreign companies and countries involved in the same film that

considerable confusion arose. The film was directed by an

Englishman, John Hough, and an Italian, Andrea Bianchi (also known

as Andrew White). The script was written by Spaniards, Italians and

Frenchmen although the original had been written by Harry, using

the penname Peter Welbeck. The role of Long John Silver was to have

been played by Yul Brynner, but due to budgetary problems we hired

Orson Welles instead. The French were represented in the cast by

Jean Lefebvre, the Italians by Rick Battaglia, the Germans by the

Austrian Walter Slezak and the Spanish by Ángel del Pozo, a ladies'

man of those times and currently a friend of mine as well as an

efficient executive at Telecinco TV.