This film's structure doesn't resemble

that of any other film made to date. In fact, what we have here are

two films running at the same time, sometimes even

simultaneously.

Regarding the first of these

films:

It is a documentary chronicling one

day in a man's life.

(There is no aspect whatsoever

about the dramatic arts -no matter how modest it might be- that

isn't based on certain rules or conventions. The filmmaker works

like a novelist. His point of view (POV) is God's point of view in

the sense that he intends to be omniscient and all knowing. The

premise is that he knows everything about the story and that what

he decides to tell viewers is a compendium of materials of his own

choice. In this film we adopt a new convention: we take God's eye

away from the filmmaker, or so it seems.

The first of our films (although

they make up a single movie) supposedly comprises the

documentary-like material that has been filmed and recorded during

the remaining hours of a man's life.

That man is J.J. Hannaford, known

to almost everybody as "Jake" Hannaford, even to the people who

have never met him, including the public.

Like Hitchcock, he was more than

just a name. Like Hemingway (who resembled him) he was, even if we

set his works aside, a world celebrity.

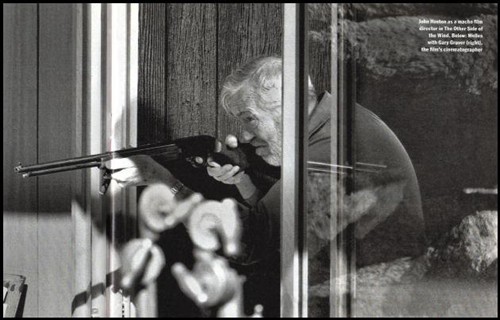

As a movie director he is one of

the few, amongst half a dozen or so, who seems to have found a

place for himself in history and who undoubtedly deserves to be

called a "great" filmmaker. As versatile as Hawks (though less

poetic), as poetic as Ford (though less sentimental), Jake

Hannaford belonged to their generation, although not really to the

same world. Like Rex Ingram (who has nearly been forgotten), Jake

was a vagabond. Most of the time, he worked as far away as possible

from California's studio world. He worked for Hollywood but took

his cameras with him all over the world. He preferred distant and

difficult places on earth because he found them more exotic. When

he wasn't in a big game hunting country, a frozen tundra or a

tropical jungle, the place he felt most at home was Spain (also

like Hemingway whom he resembled in so many ways).

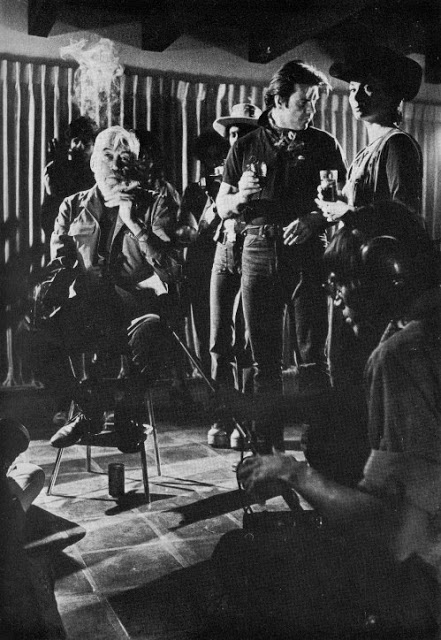

His home in America was a ranch in

the desert, and it was there where the "documentary" material that

represents our portrait of him was filmed and recorded. It happened

on the occasion of a birthday party celebrated in his honor by one

of his oldest and most loyal friends: Zarah Valeska - that fabulous

"femme fatale" from the onset of movies with sound.

Zarah had decided that the time had

come for new people from Hannaford's profession to get to know and

talk to him. Naturally, the profession was filmmaking although to

him it was more an art than a profession even though there is no

evidence that suggests that he ever referred to himself as an

artist. Although he possessed a wide-ranging and deeply-rooted

culture, he was not the least pretentious or ostentatious. On the

contrary, he often acted is if he were practically illiterate.

Obviously, a man like him had to be in open contradiction to the

new generation of filmmakers who despise cinema as an "industry"

and only respect it when it aspires to be something more "serious"

than a mere entertainment.

The birthday party Zarah Valeska

organized for him was conceived as a confrontation between Jake and

the new filmmakers from a younger generation. In that regard -like

nearly all other aspects- the party was a failure.

[...] Just as two different plots

often unfold in one musical, this movie mixes two films in

counterpoint to each other.

As we have said already, the first

film is the documentary account of the last day of Hannaford's

life.

The second film is Hannaford's own

film, i.e. the one he was making before his death; it is shown

during the action of the other film. It is shown to Hannaford's

guests in the private screening room on his ranch. Those who watch

it are characters in the other film, the documentary history. Thus

the action in the first film is an integral part of the

"documentary."

But Hannaford's film takes on a

life of its own. It tells its own independent story.

In a way, each film is a comment

about the other.

Hannaford's film narrates the

simple story about a young man and a woman (it isn't necessary to

go into details about the story here) and is conceived like a sort

of dream. Jake himself would have rejected the word "surrealism,"

but we'll have to use it to describe his last film.

As a filmmaker he always took risks

and, quite frequently, he was openly experimental. He made many

popular films, but even the commercial productions contained an

element of search, a subtle inclination to move around unexplored

regions, to find new forms and new dimensions. He wasn't an

"artistic" director (he hated that kind of thing), he was, to put

it simply, an explorer by nature, a pioneer that rode ahead of

almost all the others, always close to the border.

His last film belongs to a kind of

cinema that is very new though made by an old director. It is an

experiment and a reflection of its author.

The hero and heroine in his film

find themselves, after a series of adventures, "camping" in what

was once a movie studio, amid the remains of Chinese villages,

Persian palaces and New York slums made of inpapier machémany years

ago for long forgotten movies. They both arrive at the end of their

own story in a strange, ghostly world were nothing is or ever has

been real, and where even the illusion of reality turns to

dust.

They have, in fact, arrived at the

ruins of Hollywood.

They have arrived at the end of

Hannaford's world.

At the very end (of it all),

Hannaford has a car crash and is set ablaze.

[...] Perhaps the biggest paradox

of this paradoxical man was that Hannaford might have, in the end,

reached the point of being bored of himself.

That simple fact might lie beneath

the mystery of his suicide… if he did indeed commit suicide.

[...] He was a man who wore many

masks. At his birthday party, journalists try to tear them off him.

But do they succeed? The real mystery perhaps is not to be found in

the cause of his death but, rather, in the character of the man

himself, in the final truth about the artist, the creator of masks

behind masks. If he did indeed say everything about himself through

his art, is there anything left to be said by anyone else about

him?

Hannaford was a creator of images,

images that take on a life of their own on the screen. Was there

anything behind such images, behind the screen? Anything that

really mattered in the final analysis… other than yet another

mask?

ORSON WELLES