It soon became obvious that there

were only two countries with minimum infrastructure requirements to

carry out a complicated shoot and where it would look like the

action was taking place in Rwanda: the Ivory Coast and Senegal. The

former was discarded because the rainy season was starting at the

time we were ready to start the job. Senegal seemed like the

appropriate country to build the Rwandan scenes that Gala described

in his novel. We had photos, books and videos that had been given

to us by some missionaries and we thought that we were on the right

track.

We got in touch with the Spanish

Embassy in Dakar and the first thing they told us was that it was

not advisable for us to shoot in the southern Casamance region as

it was the nucleus of an independence movement and the previous

year the guerrillas had killed several French tourists. And yet,

according to the data at our disposal, it was precisely there where

we could find the right scenery to simulate the refugee camp in our

story.

A few of us set out to locate

suitable exterior shooting sites and to ascertain the real dangers

we might encounter if we decided to work there.

The Spaniards we met in Senegal and

who later helped us with the filming, assured us that there was no

problem at all for a film crew in Casamance. On the contrary, they

said that we would be very well received since we would employ many

local people. Besides, the story about the French tourists who had

disappeared was not very clear; in Casamance the local version held

that it was made up to discredit the separatist movement.

One only needs to glance at the map

to understand a couple of facts. Geographically, Casamance is

almost entirely separated from the rest of Senegal by Gambia.

Following the partitioning of Africa by European Colonialists - the

main cause of current conflicts, not to forget that in the

aftermath of colonialism Europeans continued selling weapons to the

Africans to kill one another - Gambia became a region of British

influence in their eagerness to find an outlet to the sea and

Casamance became part of French Senegal. This south-eastern

territory is populated by people from the Diola ethnic group (7% of

the Senegalese population), which practices a curious mix of the

Christian faith and animism. They were conquered by the French at

the end of the 19th century despite a strong resistance from

religious leaders like Fodé Kaba Doumbouya, the historic hero of

today's independence movement. Since then, and after the

independence of Senegal in the 1960s, the territory is governed

from Dakar as a Senegalese province. About 40% of Senegal's

population is part of the Wolof ethnic group and most are Muslims.

Now and again, secessionist revolts break out.

During our stay there, a guerrilla

led by a religious leader was hiding in the deep jungles that

stretch towards Guinea Bissau. However, they were in negotiations

with the central Government of Dakar to increase their local

autonomy and at the time the situation was reasonably peaceful.

With that information, we headed

for Casamance aboard the small plane that covers the route between

Dakar and Ziguinchor, the capital of the region, and which flies

over Gambia. We were very warmly welcomed. We decided that the

airport of Ziguinchor could be the starting point of the film;

Palmira Gadea's arrival in Kigali. Fascinated by what we saw, we

continued covering the whole region. It was becoming clear to us

that we should film there, although we still had to find the most

important thing of all: the refugee camp that appears at the end of

the movie. Every day we'd clear several military checkpoints and

carried on with our job.

During this first location search,

we only had one major scare. It happened one day at dusk when the

accursed Anopheles malaria-transmitting mosquito becomes active. On

our way back to the hotel, we stopped to watch an animist ceremony.

Our Senegalese driver tried to deter us on the grounds that it

wasn't something touristic but rather, a very serious ritual: the

ritual of the "crazy lion". His explanation just made us more

curious, so we got out of the jeep without the driver - nothing in

the world could persuade him to join us - and walked to a field

near a settlement where, by the light of several bonfires, the

ritual was taking place. Amid a circle of people, the "Lion

Priests" belonging to a caste that exclusively devotes itself to

these rituals, jumped up and down in a violent ballet, their faces

painted, dressed like wild animals, with blood-shot eyes- screaming

like epileptics and terrifying all those present. Meanwhile,

another "priest" -a transvestite-like character- was directing the

show. We were advised to buy ourselves a little piece of paper with

some signs written on the back, which an acolyte was ripping out of

a notebook, as a means of protecting ourselves from a potential

clawing swipe from the odd performer who might not like us. And so

we did.

Suddenly, the "crazy lions" exited

the circle. Some of them took off towards the settlement. Others

stayed there, in a trance, hardly moving. The first lot however,

pounced on whoever didn't show to them the "ticket-óbolo" and

dragged the victim towards the circle, until he paid up or the

"lion" got tired. There were some children there who, while the

priests "played" at eating them, got so frightened that they peed

their pants until their mother turned up and, after paying their

dues, rescued her poor offspring. We were standing there motionless

with our little paper well in sight just in case, and glancing at

each other out of the corner of our eyes. Mind you, they soon

enough spotted us and approached. They surrounded us and roared a

few inches away from our faces. Pity we couldn't take a snapshot or

two of that moment although it most certainly wasn't the right time

to be a foreigner or tourist. There we were, scared as hell and

pathetically showing them our little papers until they left us

alone. We retreated as discreetly as we could towards the jeep,

where our driver was waiting for us, looking worried. As he turned

on the engine, it was nightfall, but the "crazy lions" continued

terrifying the neighborhood.

At length, we arrived at Cap

Skining. Relatively near there - I say this for the benefit of any

atypical tourist who might be eager to dive into this amazing world

- there are cabins where one can practice an integration type of

tourism. Anyway, soon enough Diembering came into view, with its

sacred forest of millenary trees. There was our perfect location

for the refugee camp. At last we had found our African exterior

location for the film.

Upon our return to Madrid, we

continued working on the film. While we toured Seville - where the

only difficult thing was to find Palmira's garden - the guys from

the production department spoke once more with the Spanish Embassy.

Again, the ambassador didn't approve and said the Embassy could not

guarantee our safety if we insisted on filming in Casamance. But

the decision had already been made. The entire crew had to sign a

document stating that we would be responsible for anything that

might happen to us. That done, and having been vaccinated against

many different illnesses and equipped ourselves

withdifficult-to-digestmalaria pills, we returned to start shooting

the film.

It took time before we met the

Ambassador. During the time we were engaged in locating sites for

shooting exteriors, he apparently had to accompany some Spanish

friends who wanted to tour around Saint Louis, a beautiful colonial

city in northern Senegal. And when we began filming, he only

appeared once on the island of Gorée, near Dakar, where we were

working on the initial scenes of the film; the ones in which the

mission where Palmira works as a nurse appears. The Ambassador had

lunch with us and had many photos of himself taken with Concha

Velasco for the magazines and news agencies that were following the

shooting. When we went back to Spain, once in Seville, we cracked

up laughing when we read that we had worked with the full support

of the Spanish Embassy in general and of the Ambassador in

particular.

The most thrilling filming was done

in Casamance. The equipment - a double set of cameras, the power

pack, dollies, crane, etc., had arrived by ship while most of us

travelled in small groups, by regular airline plane or on small

planes. Others travelled on trucks, crossing over the river

Gambia.

Our starting point was Ziguinchor,

with the sequences of Palmira arriving in Rwanda. We needed

soldiers, to create the impression that the airport had been taken

over by the military, and we were able to obtain the collaboration

of the Senegalese army. They say that military logic is to logic

what military logic is to music and the saying was no exception

over there: the soldiers wanted to appear in the film dressed

impeccably in their best military clothes like when on parade. We

had to tell them repeatedly that we were doing a film about the war

in Rwanda, not a report about the virtues of the Senegalese army.

We had to resort to the highest circles at the governmental level

to obtain permits for them to wear clothes from our own wardrobe

during the shooting. And the truth is that they performed very

well.

But later on, regardless of whether

we needed them anymore or not, they accompanied us throughout the

rest of the shooting for security reasons. In the end, we arrived

in Diomboring, where we worked with over one thousand extras from

the Independence region.

There were cases of alleged

guerrilla fighters who, upon leaving jail, would immediately join

the others as an extra. A female colleague from the crew told us

she had gotten to know one of the extras and ended up going with

him to his hut. The decoration was very simple: a worn-out

mattress, a table, a poster of Wojtyla on the wall and a submachine

gun in a corner. She asked him if the weapon was from the filming,

and he replied convincingly: "No, it's mine."

We were worried that in the final

scenes - with Senegalese soldiers playing the role of Tutsis and

"firing" at others who played Hutus - an incident or confrontation

might occur and that we might in the end have to acknowledge that

at least partly, the Spanish Embassy was right in its warnings. But

as it turned out, there was not the slightest trouble. We explained

clearly to everyone what we wanted to convey in the film to ensure

that everything went well.

And thus we carried on working

until the end, getting on well with the Senegalese team and doing

what I think was a good job: sometime we commented amongst us what

filming "Out of Africa" must have been like, with their impressive

display of super-air conditioned caravans. We ourselves only had

one caravan and the A/C never worked. But we only envied them to a

certain extent because it must be admitted that our experience was

extraordinary in many different ways.

Now, every time I have to see the

film, I can't help feeling moved, not because of the film in

itself, but because of all that lies behind every shot we filmed in

Senegal. It was certainly worthwhile.

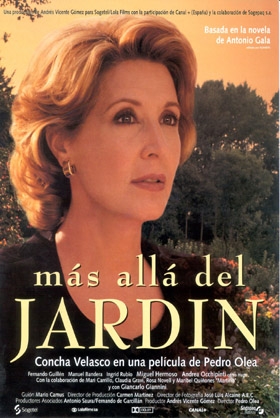

PEDRO OLEA.